Decanting

Wine decanters have a certain sophistication and class about them. In fact, I'm fairly convinced that merely setting an elegant and graceful decanter down on the table ensures that your guests think better of your wine. Aesthetics aside, there are significant benefits to the decanter.

Aerating and decanting are often conflated. The goal of aeration is to soften tannins and oxidize non-integrated flavors in a young wine, making it smoother and rounder. Decanting claims to remove sediment from a wine and is typically necessary for an older or unfiltered wine. The traditional decanter, with a wide base and narrower neck, is an excellent aerator as well, providing a large surface area of wine to have contact with oxygen.

Oxygen affects many organic compounds in wine and exposure to air in wine is a delicate balance. For a young big, brawny red, like a Syrah or Bordeaux, aerating is most definitely worth the effort. In order to achieve ideal results you may need to let the wine sit an hour or two. In aerating, one is looking for the sweet spot where unwanted characteristics have oxidized out of the wine, but the fruit and minerality are present.

There is some debate whether tannins are truly impacted by aeration. A tannin is a protein string and the tannic note in a wine is the tongue's perception of the receptors at the end of the tannin string. The aging of a wine in a barrel promotes a slow exchange of oxygen and over time the oxygen will encourage the polymerization of tannins (i.e. promote the bonding of small strings into longer strings). Longer, bonded strings mean less individual strings which means less ends of strings whose astringency can overwhelm a wine. Long aging processes are the tried and true method of creating longer strings which will retain the structure and provide some tannic notes, but arguments are made that aerating can do wonders to soften tannins and round out a wine. Wines that feel closed or tight often benefit from aeration.

Comparatively, a wine that is more likely to be in need of decanting is all the more sensitive to aeration. Sediment is a natural occurrence in wine and is completely harmless. That said, texturally alone, it is off putting in a glass of wine and sometimes sediments can have unpleasant, bitter flavors to them. In older wines, where the chance of sediment development is greater, it becomes critical to decant your wine. There are 2 major types of wine sediment, colloids and tartrates. The first sediment is comprised of organic compounds such as proteins (like tannins), polysaccharides and pigments. These form slowly in bottles meant to be aged. The second type is caused by the formation of potassium bitartrate crystals (cream of tartar) from the potassium and the tartaric acid found in grapes. This process is forwarded by cooler temperatures and many wine makers will seek to subject barrels to cooler temperatures, attempting to remove the sediment prior to bottling. This is referred to as "salting out". Red wines are less likely to have fully salted out in barrel due to a higher alcohol content.

Sediment is both natural and desirable in an aged bottle of red wine. However, it also indicates a mature bottle of wine that may suffer from prolonged exposure to oxygen. Aerating is a gamble to balance a wine, hoping that the harsher flavors will oxidize out before the fruit will. In a mature wine, tannins have mellowed, organic compounds have settled and often what's left in line to oxidize is the fruit itself!

To treat your nicely aged red well, leave the bottle upright for 3 or 4 days to ensure that all sediment has settled at the bottom. Sometimes it is possible to see sediment by shining a flashlight on the other side of the bottle. In general, red wines begin to develop sediment between 5-10 years. The only surefire way to decide how long to aerate a wine for is to taste it. Once the sediment has been allowed to settle, carefully open the bottle and taste a small amount of wine. If the wine feels full and mature, decant immediately before serving. If the wine is closed or inexpressive, decant for a period of time.

Like everything else in wine, degree of aeration in an individual wine is subject to one's palate and environment. Aerators and decanters are useful tools for understanding the interaction of wine and oxygen. Play with them to develop a sense of your personal taste!

Wine decanters have a certain sophistication and class about them. In fact, I'm fairly convinced that merely setting an elegant and graceful decanter down on the table ensures that your guests think better of your wine. Aesthetics aside, there are significant benefits to the decanter.

Aerating and decanting are often conflated. The goal of aeration is to soften tannins and oxidize non-integrated flavors in a young wine, making it smoother and rounder. Decanting claims to remove sediment from a wine and is typically necessary for an older or unfiltered wine. The traditional decanter, with a wide base and narrower neck, is an excellent aerator as well, providing a large surface area of wine to have contact with oxygen.

Oxygen affects many organic compounds in wine and exposure to air in wine is a delicate balance. For a young big, brawny red, like a Syrah or Bordeaux, aerating is most definitely worth the effort. In order to achieve ideal results you may need to let the wine sit an hour or two. In aerating, one is looking for the sweet spot where unwanted characteristics have oxidized out of the wine, but the fruit and minerality are present.

There is some debate whether tannins are truly impacted by aeration. A tannin is a protein string and the tannic note in a wine is the tongue's perception of the receptors at the end of the tannin string. The aging of a wine in a barrel promotes a slow exchange of oxygen and over time the oxygen will encourage the polymerization of tannins (i.e. promote the bonding of small strings into longer strings). Longer, bonded strings mean less individual strings which means less ends of strings whose astringency can overwhelm a wine. Long aging processes are the tried and true method of creating longer strings which will retain the structure and provide some tannic notes, but arguments are made that aerating can do wonders to soften tannins and round out a wine. Wines that feel closed or tight often benefit from aeration.

Comparatively, a wine that is more likely to be in need of decanting is all the more sensitive to aeration. Sediment is a natural occurrence in wine and is completely harmless. That said, texturally alone, it is off putting in a glass of wine and sometimes sediments can have unpleasant, bitter flavors to them. In older wines, where the chance of sediment development is greater, it becomes critical to decant your wine. There are 2 major types of wine sediment, colloids and tartrates. The first sediment is comprised of organic compounds such as proteins (like tannins), polysaccharides and pigments. These form slowly in bottles meant to be aged. The second type is caused by the formation of potassium bitartrate crystals (cream of tartar) from the potassium and the tartaric acid found in grapes. This process is forwarded by cooler temperatures and many wine makers will seek to subject barrels to cooler temperatures, attempting to remove the sediment prior to bottling. This is referred to as "salting out". Red wines are less likely to have fully salted out in barrel due to a higher alcohol content.

Sediment is both natural and desirable in an aged bottle of red wine. However, it also indicates a mature bottle of wine that may suffer from prolonged exposure to oxygen. Aerating is a gamble to balance a wine, hoping that the harsher flavors will oxidize out before the fruit will. In a mature wine, tannins have mellowed, organic compounds have settled and often what's left in line to oxidize is the fruit itself!

To treat your nicely aged red well, leave the bottle upright for 3 or 4 days to ensure that all sediment has settled at the bottom. Sometimes it is possible to see sediment by shining a flashlight on the other side of the bottle. In general, red wines begin to develop sediment between 5-10 years. The only surefire way to decide how long to aerate a wine for is to taste it. Once the sediment has been allowed to settle, carefully open the bottle and taste a small amount of wine. If the wine feels full and mature, decant immediately before serving. If the wine is closed or inexpressive, decant for a period of time.

Like everything else in wine, degree of aeration in an individual wine is subject to one's palate and environment. Aerators and decanters are useful tools for understanding the interaction of wine and oxygen. Play with them to develop a sense of your personal taste!

by Kerry Hoeschen

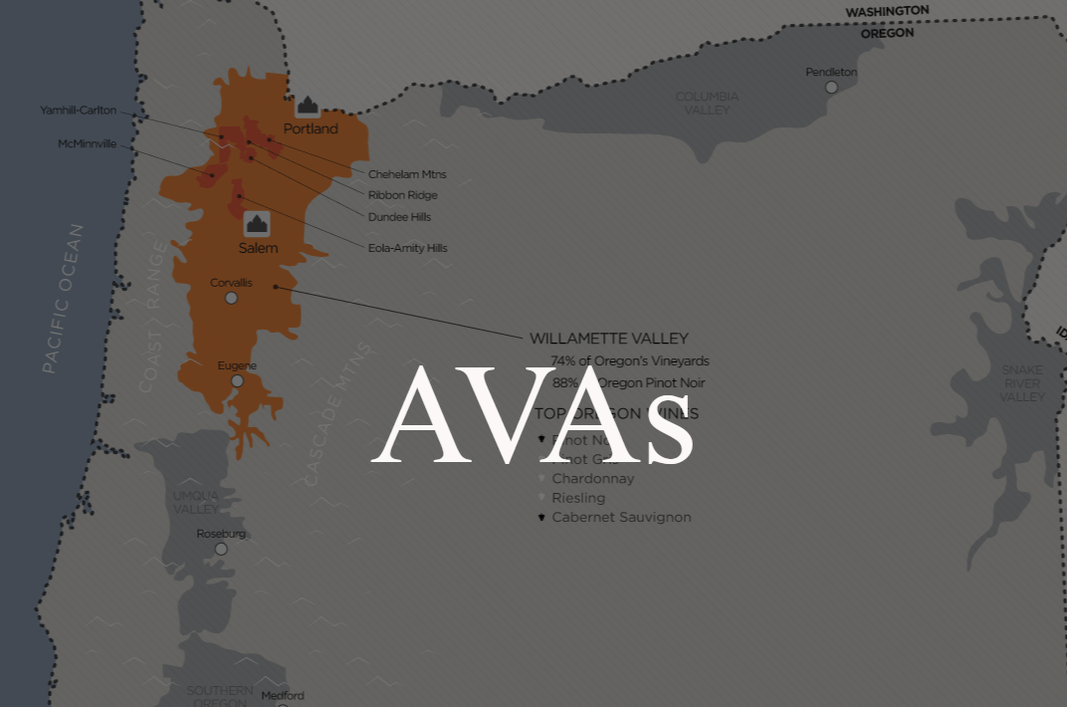

The Four Graces

9605 NE Fox Farm Rd.

Dundee, Oregon 97115Tel: 503.554.8000

Fax: 503.554.0632

The Four Graces

9605 NE Fox Farm Rd.

Dundee, Oregon 97115Tel: 503.554.8000

Fax: 503.554.0632